Did the cheetah once live in California—and why is the American pronghorn SO fast?

For years, scientists believed Miracinonyx trumani—North America’s so-called cheetah—was a high-speed predator that shaped the pronghorn’s evolution. But new fossil discoveries, stretching from the Great Plains to California, reveal a more complex story.

The American pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) holds the title as the second-fastest land animal, reaching speeds of up to 55 mph.

Far exceeding that of any North American predator, the pronghorn’s extraordinary speed has long posed an evolutionary mystery: What predators once hunted it?

Adding to the intrigue is the historical debate over whether a cheetah-like feline once roamed North America.

The African cheetah, known for breathtaking top speeds up to 75 mph, is not only Earth's fastest land mammal, but the only living predator that can come close to outpacing the pronghorn. In modern Africa, cheetah prey on small antelope, which can appear, particularly to the untrained eye, comparable to the the American pronghorn.

Paleontologists have thus speculated for years that a direct ancestor of the cheetah, if not the modern cheetah itself, held an ancestral presence in North America, including modern-day California.

Closely related is the long-permeating theory that the pronghorn can run 50+ mph because it evolved to survive the cheetah, the pronghorn's speed becoming redundant when the cheetah migrated to Asia, then Africa, via the Bering land bridge around 10,000 years ago.

But fossil evidence suggests a different story—one that involves an entirely separate species called Miracinonyx trumani, an extinct feline that evolved independently of African cheetahs.

This article will explore whether the African cheetah ever lived in California, the role of Miracinonyx trumani in North America’s Pleistocene ecosystems, and whether the pronghorn still carries the legacy of an ancient high-speed chase.

The True Nature of Miracinonyx trumani

Rethinking the “American Cheetah”

For decades, the extinct Miracinonyx trumani has been portrayed as North America’s version of the African cheetah—an ultra-fast predator that once roamed the plains in pursuit of pronghorns (Antilocapra americana).

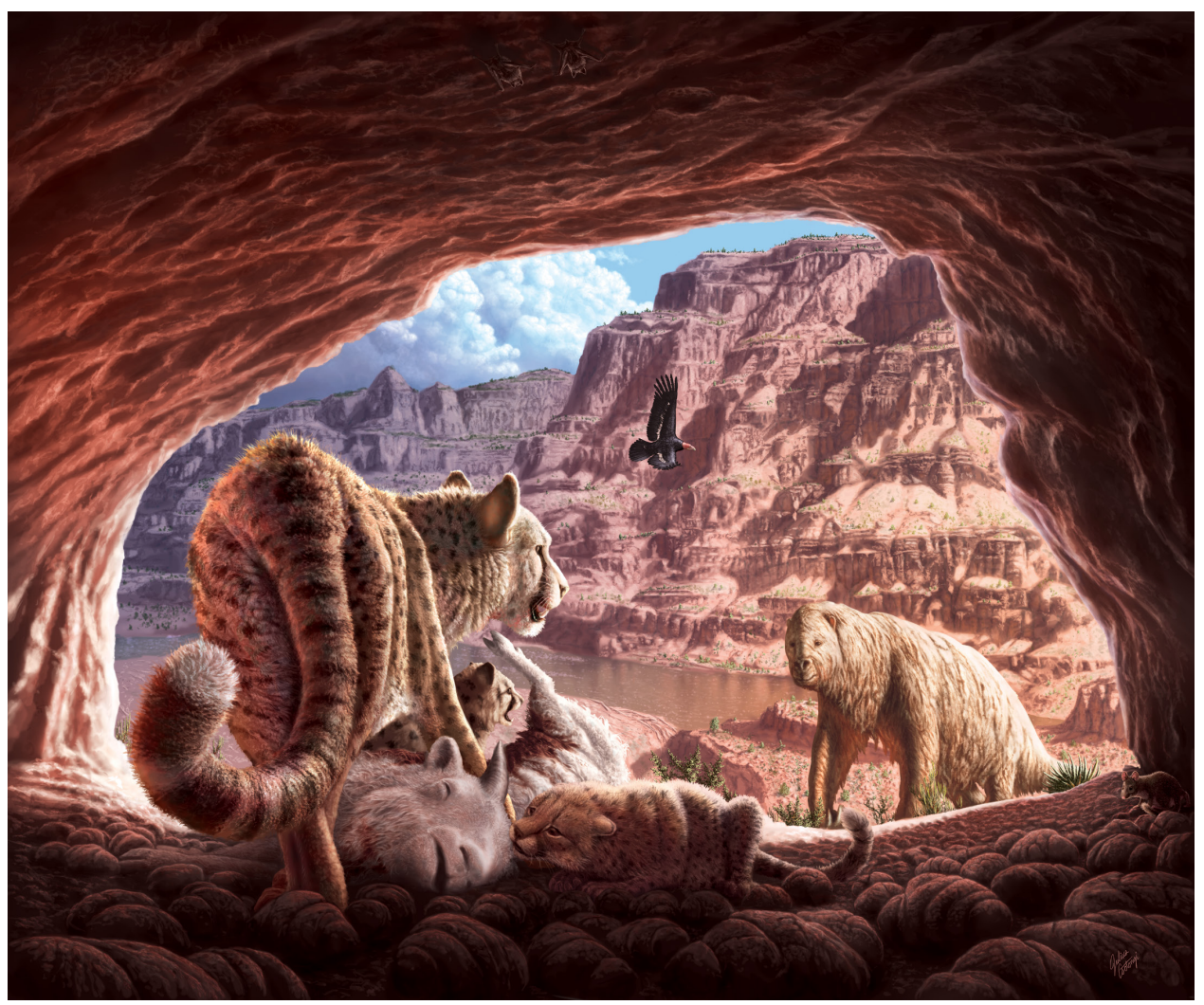

However, fossil evidence from the Grand Canyon is rewriting the story of this enigmatic predator.

"The presence of Miracinonyx within the Grand Canyon raises questions about the ecology of this large cat. Previously, Miracinonyx was proposed as a cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) ancestor or an unrelated felid which co-evolved a cheetah-like ecology hunting prey in open savanna-like habitats."

-Hodnett et al., 2022

Rather than a sprinting specialist of open grasslands, Miracinonyx may have been more at home among rocky cliffs, resembling modern snow leopards in its hunting strategies.

New Fossil Discoveries in the Grand Canyon

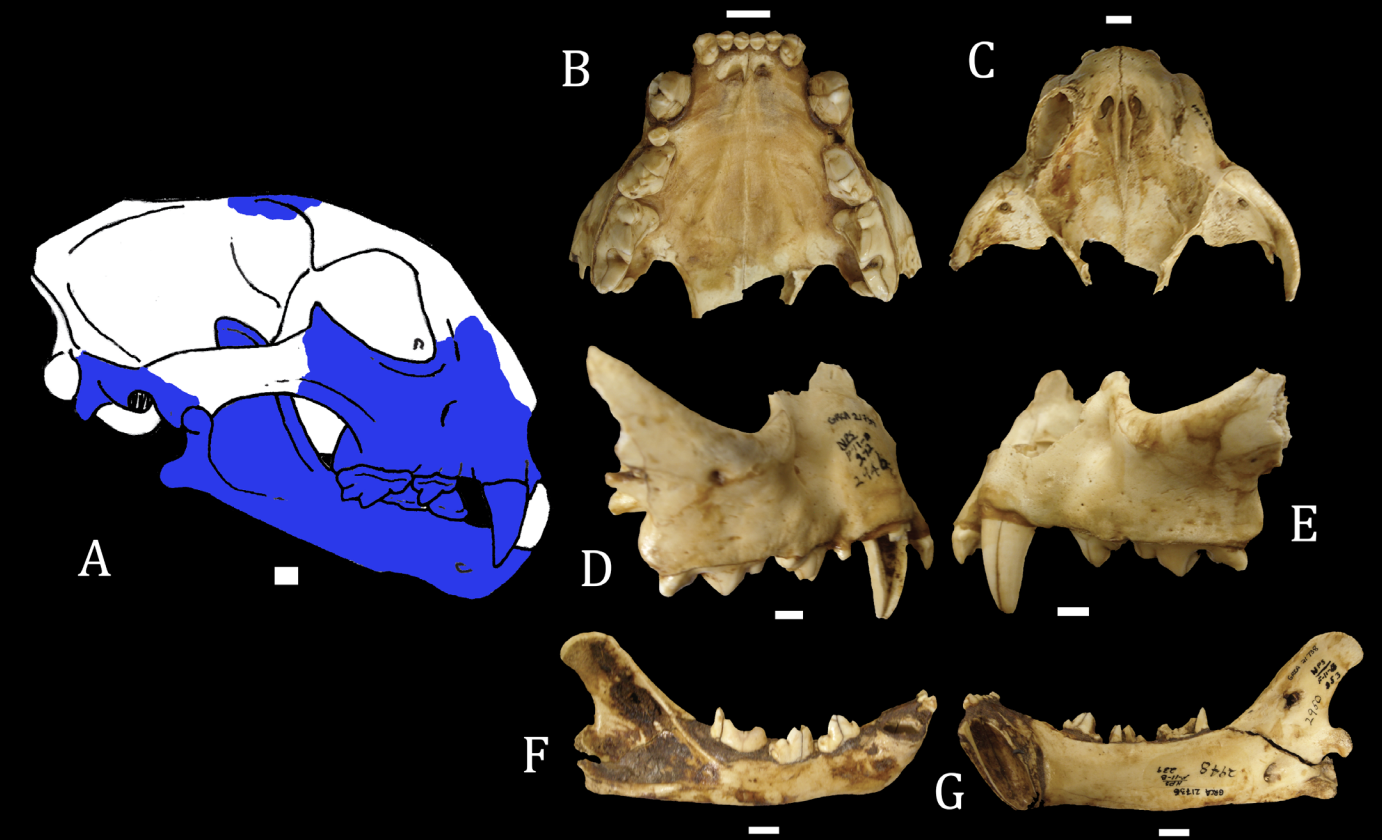

Discoveries from three Grand Canyon fossil sites—Rampart Cave, Next Door Cave, and Stanton’s Cave—confirm the presence of Miracinonyx trumani in a region where it was previously thought that only mountain lions (Puma concolor) existed. The fossils include skull fragments, limb bones, and even fossilized feces (coprolites), providing an unprecedented look at the ecology of this extinct feline.

One of the most striking findings is that past fossil identifications of Puma concolor from the region may have been incorrect. Researchers now argue that these remains belong to Miracinonyx. “Our recent review of the Grand Canyon P. concolor remains suggests that the designation of a Rancholabrean P. concolor at the Grand Canyon is incorrect,” the study states. “We contend that there is no late Pleistocene record of P. concolor for the Grand Canyon”.

A Closer Look at Miracinonyx trumani

Physically, Miracinonyx trumani shared some traits with modern cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus), such as long limbs and a lightweight, gracile frame built for speed. However, genetic studies reveal that Miracinonyx was actually more closely related to mountain lions than to cheetahs. This suggests that its similarities to African cheetahs arose through convergent evolution, where unrelated species develop similar traits due to similar ecological pressures.

Unlike cheetahs, Miracinonyx trumani did not live in vast savannas or open plains. Instead, it seems to have thrived in rugged, mountainous terrain.

“The occurrence of the fossil remains of M. trumani within the canyon itself raises the possibility that this felid was adapted for a habitat that was composed of closed woodlands and rocky steep surfaces with prey that were adapted to those conditions."

-Trayler et al., 2025

The Grand Canyon fossils suggest that rather than chasing pronghorns across open landscapes, Miracinonyx was more likely stalking and ambushing prey in rocky environments.

Did the African Cheetah Ever Live in California?

The short answer is no—there is no fossil evidence to suggest that the African cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) or any direct ancestor of it ever lived in North America. Instead, North America had its own cheetah-like predator: Miracinonyx trumani, sometimes referred to as the "American cheetah."

The Fossil Evidence from California

Fossilized remains of Miracinonyx trumani have been found at multiple sites in California, particularly at Rancho La Brea in Los Angeles and the McKittrick Tar Seeps in Kern County (Trayler et al., 2025).

These discoveries initially led to some confusion, as some of the remains were originally classified as belonging to Puma concolor (mountain lion). However, further analysis confirmed that certain specimens were actually Miracinonyx trumani, revealing that this species had a presence in late Pleistocene California.

Although Miracinonyx shared some physical similarities with African cheetahs—such as long limbs, a lightweight frame, and a deep chest—it was actually more closely related to modern mountain lions (Puma concolor). The resemblance between Miracinonyx and Acinonyx jubatus is a classic example of convergent evolution, where unrelated species develop similar traits due to similar ecological pressures.

Why Is the Pronghorn So Fast?

A closer look at the The Evolutionary Arms Race Hypothesis

The American pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) is one of the fastest land mammals, capable of reaching speeds up to 55 mph. It is second only to the African cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus), which can sprint at an astonishing 75 mph in short bursts (Higgins et al., 2023). Unlike the cheetah, which relies on speed to hunt, the pronghorn has no modern predator that can match its velocity.

This raises an evolutionary puzzle: if no living predator can keep up, why did the pronghorn evolve such extreme speed?

The Evolutionary Arms Race Hypothesis

For many years, the dominant theory was that pronghorns evolved their speed to escape from Miracinonyx trumani, which was believed to be a high-speed pursuit predator similar to the African cheetah. This idea was supported by fossil evidence from Natural Trap Cave in Wyoming, where isotopic analysis confirmed that Miracinonyx preyed on pronghorns—though not exclusively (Higgins et al., 2023). Researchers found that Miracinonyx’s diet also included bison, horses, and bighorn sheep, indicating that it was a versatile predator.

However, new fossil evidence has complicated this picture. Research from the Grand Canyon suggests that Miracinonyx may not have been a specialized sprinting predator at all. Instead, it may have lived in rocky, mountainous regions and used ambush tactics to hunt (Hodnett et al., 2022).

If Miracinonyx was not exclusively a high-speed predator, this raises the question: Did pronghorns evolve their speed for reasons beyond escaping this extinct feline?

Alternative Explanations for Pronghorn Speed

Some scientists now believe that pronghorns evolved their speed due to multiple ecological pressures rather than a single predator-prey relationship. Potential factors include:

- Escaping multiple predators: In addition to Miracinonyx, prehistoric wolves (Canis spp.) and North American lions (Panthera atrox) may have also exerted selective pressure on pronghorn speed. Modern gray wolves (Canis lupus) can reach speeds of up to 40 mph in short bursts, but they primarily rely on endurance hunting rather than sprinting (Higgins et al., 2023). North American lions, likely ambush predators, had unknown but presumably slower chase speeds compared to Miracinonyx.

- Environmental conditions: During the Pleistocene, North America’s open grasslands provided little cover, making speed one of the most effective survival strategies against various predators.

- Sexual selection: Some researchers have proposed that fast-running males had better success in mating, leading to an evolutionary preference for speed over many generations.

While Miracinonyx may have contributed to the pronghorn’s remarkable running ability, it was likely not the sole evolutionary force behind it.

What We Know and What We Don't

The African cheetah never lived in North America, but Miracinonyx trumani—a felid that evolved cheetah-like traits through convergent evolution—once roamed California and other parts of North America. Although fossil evidence initially supported the idea that Miracinonyx was a plains-dwelling sprinter that drove pronghorn evolution, recent discoveries in the Grand Canyon and California suggest that it may have been a more versatile predator, capable of ambush hunting in rugged landscapes (Hodnett et al., 2022; Trayler et al., 2025).

As for the pronghorn, its incredible speed remains a biological mystery. While Miracinonyx likely played a role in shaping its evolution, new evidence suggests that pronghorn speed may have resulted from multiple factors, including escaping various predators, adapting to open environments, and even sexual selection (Higgins et al., 2023).

Even though Miracinonyx trumani vanished from North America over 10,000 years ago, its possible role in shaping the pronghorn’s unmatched speed endures. Today, when pronghorns sprint across the Great Plains at breathtaking speeds, they are not just running for survival—they are running with the echoes of their ancient predators.