Coyotes are one of the most adaptable carnivores in North America, thriving across deserts, forests, grasslands, and even the densest urban neighborhoods. Once restricted to the open prairies and deserts of the continent, coyotes have expanded their range dramatically and are now present in nearly every ecosystem of California.

This adaptability makes coyotes both ecologically important and a frequent source of conflict with people. By understanding their biology and behavior, Californians can better appreciate their role in the environment while learning strategies to reduce negative interactions and promote coexistence.

Sources and References for Our Coyote Coverage

Our coyote hub is based on trusted resources from government agencies, universities, and peer-reviewed research. Explore the full list below:

- National Park Service (NPS) – Coyote Information Page

- California Department of Fish & Wildlife (CDFW) – Wildlife Incident Reporting (WIR) System

- California Fish & Game Commission – Nongame Animal Regulations

- UC IPM – Pest Notes: Coyotes

- USDA APHIS – Wildlife Damage Management Technical Series: Coyotes (PDF)

- Project Coyote – Be Coyote Aware Flyer (PDF)

- California Department of Fish & Wildlife / Human–Wildlife Conflict Program – Coyote Management Plans and Wildlife Watch (PDF)

- California Department of Fish & Wildlife – Coyote Range Map (PDF)

- UC ANR – Publication 8598: Livestock Protection Tools for California Ranchers (PDF)

- Scientific Reports (2024) – Urban coyotes in southern California show adaptations to anthropogenic landscapes and activity patterns

- Ecology Letters (2025) – Environmental Health and Societal Wealth Predict Movement Patterns of an Urban Carnivore

Identification & Physical Characteristics

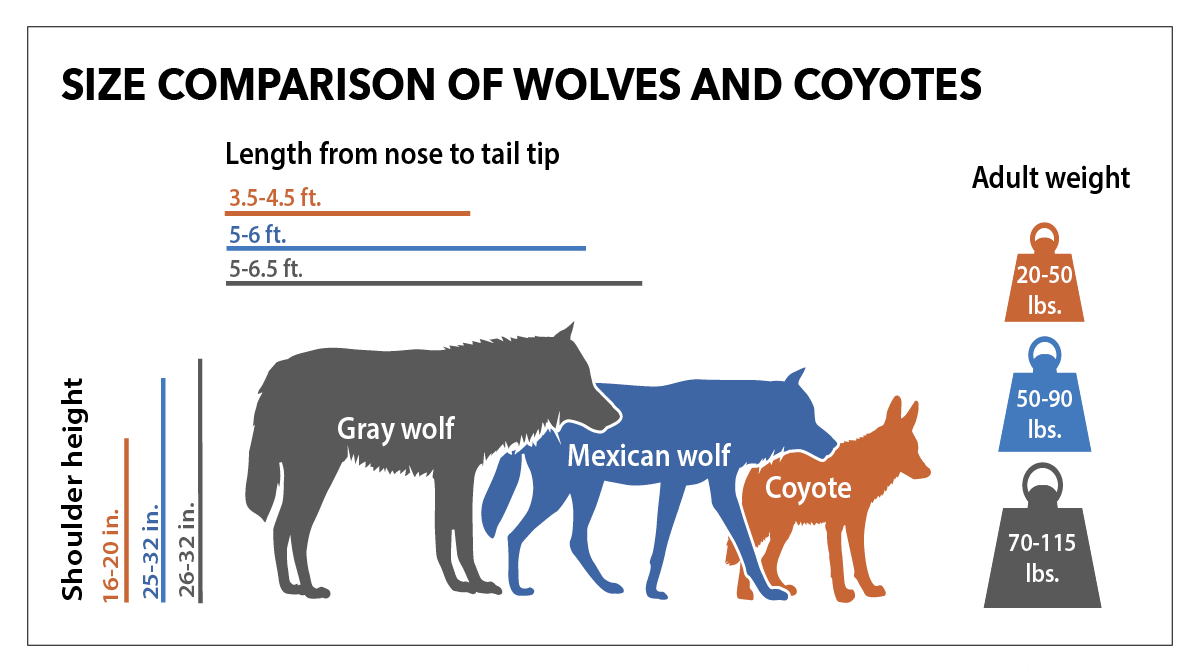

Coyotes are medium-sized canids, typically standing 2–3 feet tall at the shoulder, with a 16–20 inch bushy tail and weighing between 25–35 pounds. Their fur is often a grizzled gray, tan, or light brown with a distinct black-tipped tail, which is one of their most recognizable features.

They are frequently confused with dogs or wolves, but behavior and posture help distinguish them.

- Dogs usually run with their tails up.

- Wolves hold their tails straight behind them.

- Coyotes run with their tails down, a subtle but consistent identifier.

Regional variation exists across California. Desert coyotes tend to be smaller and leaner, adapted to arid environments, while mountain and coastal coyotes are generally larger and stockier, with thicker coats to withstand colder, wetter conditions.

Life Cycle & Reproduction

Coyotes follow a seasonal reproductive cycle that helps them adapt to California’s varied climates. Breeding usually occurs in February or March. Dens are often dug into hillsides, enlarged from old burrows, or located under brush and fallen logs, providing protection for pups during their first vulnerable weeks.

A typical litter contains 5–7 pups, although litters may range in size depending on food availability. Both parents participate in rearing, and older siblings may remain with the family group to help feed and protect pups. This cooperative structure increases survival rates, especially in areas where food resources are abundant.

Coyotes' average life span in the wild usually live 6–8 years, but in urban or protected environments, some individuals may reach 10–14 years. High mortality from vehicles, disease, and conflict with humans remains the main limiting factor on lifespan.

Diet & Feeding Behavior

Coyotes are opportunistic omnivores, meaning they will eat whatever is most available at a given time. Their diet in California typically includes:

- Small mammals such as rabbits, ground squirrels, and rodents.

- Reptiles, amphibians, and insects, especially in warmer months.

- Birds and carrion when encountered.

- Seasonal fruits and grasses, such as berries and persimmons, particularly in fall and winter.

In rural and wildlands, rodents and rabbits form the dietary core. In contrast, urban coyotes often shift toward anthropogenic food sources—garbage, pet food, compost, unsecured fruit trees, and even domestic pets. Studies in Southern California have shown coyotes consuming food waste at high rates, with behavior shifting toward nocturnal foraging to reduce human encounters.

This dietary flexibility allows coyotes to thrive across the state, from deserts to cities, reinforcing their reputation as one of the most adaptable carnivores in North America.

Social Behavior & Communication

Coyotes are highly social, but unlike wolves they do not form large, stable packs. Instead, they live in family groups, typically consisting of a mated pair and their offspring from the current year, sometimes with older siblings that remain to help rear pups. While coyotes often hunt alone or in pairs, they may work cooperatively when taking down larger prey or when scavenging. Remarkably, they have even been observed hunting cooperatively with badgers, where the coyote flushes prey from burrows while the badger digs from below.

Territories are defended by scent-marking and vocal displays. Coyote home ranges vary widely: in California, rural ranges can span 10–40 square miles, while in cities, ranges may shrink to 2–10 square miles due to higher food availability.

Communication is central to coyote life. They are among the most vocal of North America’s mammals, producing howls, yips, barks, and growls. These calls serve multiple purposes: reinforcing family bonds, marking territory, warning intruders, and coordinating activities. In California, coyotes are most often heard at dusk and dawn, with group choruses giving the impression of larger numbers than are actually present.

Ecology & Role in California Ecosystems

Coyotes are keystone mesopredators, playing a vital role in regulating prey populations and influencing ecosystem balance. By consuming large numbers of rodents and rabbits, they help limit agricultural pests and maintain vegetation health. In agricultural and rangeland areas, their predation on rodents can be beneficial, though this role is often overshadowed by conflicts with livestock.

Coyotes also interact with other predators. In much of California, they overlap with bobcats, gray foxes, and mountain lions. Coyotes often displace smaller predators such as foxes through competition, while mountain lions remain dominant over coyotes. In some ecosystems, however, coyotes function as the apex predator, particularly in fragmented urban areas or island-like habitats, where larger carnivores are absent.

Recent studies suggest coyotes can have cascading ecological impacts. For instance, where coyotes suppress domestic cats in urban areas, native songbirds and small mammals may benefit. Conversely, in places where coyotes are heavily controlled, smaller mesopredators may increase, creating imbalances. This dual role underscores their ecological complexity in California’s diverse habitats.

Adaptations for Survival

Coyotes’ success in California is rooted in their extraordinary adaptability. They adjust their behavior, diet, and activity patterns to match local conditions, allowing them to persist in deserts, mountains, farmlands, and dense urban centers alike.

Key adaptations include:

- Dietary flexibility: From rodents and deer carrion in rural areas to fruit trees, garbage, and even domestic pets in cities.

- Behavioral shifts: Urban coyotes often become nocturnal to avoid humans, while rural coyotes may remain active throughout the day.

- Use of corridors: In fragmented city landscapes, coyotes travel along rivers, flood channels, railways, and greenbelts, effectively navigating built environments.

- Reproductive resilience: When populations are reduced through lethal control, coyotes respond with higher reproductive rates and pup survival, quickly compensating for losses.

These adaptations ensure that attempts at eradication have historically failed and that coyotes remain one of California’s most enduring carnivores.

Conclusion

Coyotes in California embody resilience. Their flexible diet, social structure, and ability to adapt to both wild and urban environments make them a permanent fixture across the state. While they can create challenges for livestock producers and suburban communities, they also provide valuable ecological services as rodent controllers and scavengers.

By understanding their biology and natural history, Californians gain the foundation needed to approach coyote management with balance—recognizing both the conflicts they cause and the ecological roles they fulfill.

Learn More About California Coyotes